A popular way to explain climate change is “the bathtub analogy.”

The explanation goes like this: Imagine that the atmosphere is a bathtub rapidly filling with water. (In this case, the water is greenhouse gasses like carbon dioxide and methane.) The goal is to stop the bathtub from overflowing, which in this metaphor, represents the global temperature increasing to unsafe levels, especially for the most vulnerable countries. One way to stop the overflow is by turning off the faucet – to stop polluting.

Avoiding emissions from fossil fuels (the faucet problem) is always a major topic of conversation at the United Nations annual climate change conference and obviously, reducing carbon emissions is crucial. It’s the vast majority of what we focus on at Breakthrough Energy. But focusing on carbon mitigation exclusively at COP28 this November is a disservice to people around the world who will suffer the most from climate change.

Even when the world stops emitting, there will still be more than a century’s worth of greenhouse gasses left in the bathtub because unlike some other pollutants, CO2 doesn’t leave the air quickly. In fact, it sticks around for centuries and keeps our planet warmer than we’d like. That means the air today contains carbon from bombers in World War II and factories from the industrial revolution. The truth is we can’t afford to just find ways to stop polluting – we have to clean up the mess too.

Yet that reality can be contentious. Why? Some experts worry the ability to clean up will compel people to keep running the spigot. In other words, they believe it could be used as an excuse or “social license” to continue burning fossil fuels and emitting CO2. Why turn off the water when we can just mop it up?

This concern is understandable. But, decades ago, advocates once rejected adaptation and resilience for the same reason—they feared that talking about adapting to climate impacts would erode the urgency to mitigate the fossil fuel emissions that cause the impacts. Thankfully, countries and climate advocates now all embrace the need to adapt to the effects of warming, especially for the most vulnerable nations. We should do the same for carbon removal, as limiting warming to well below 2.0°C – the goal we established in Paris eight years ago – is virtually impossible without it.

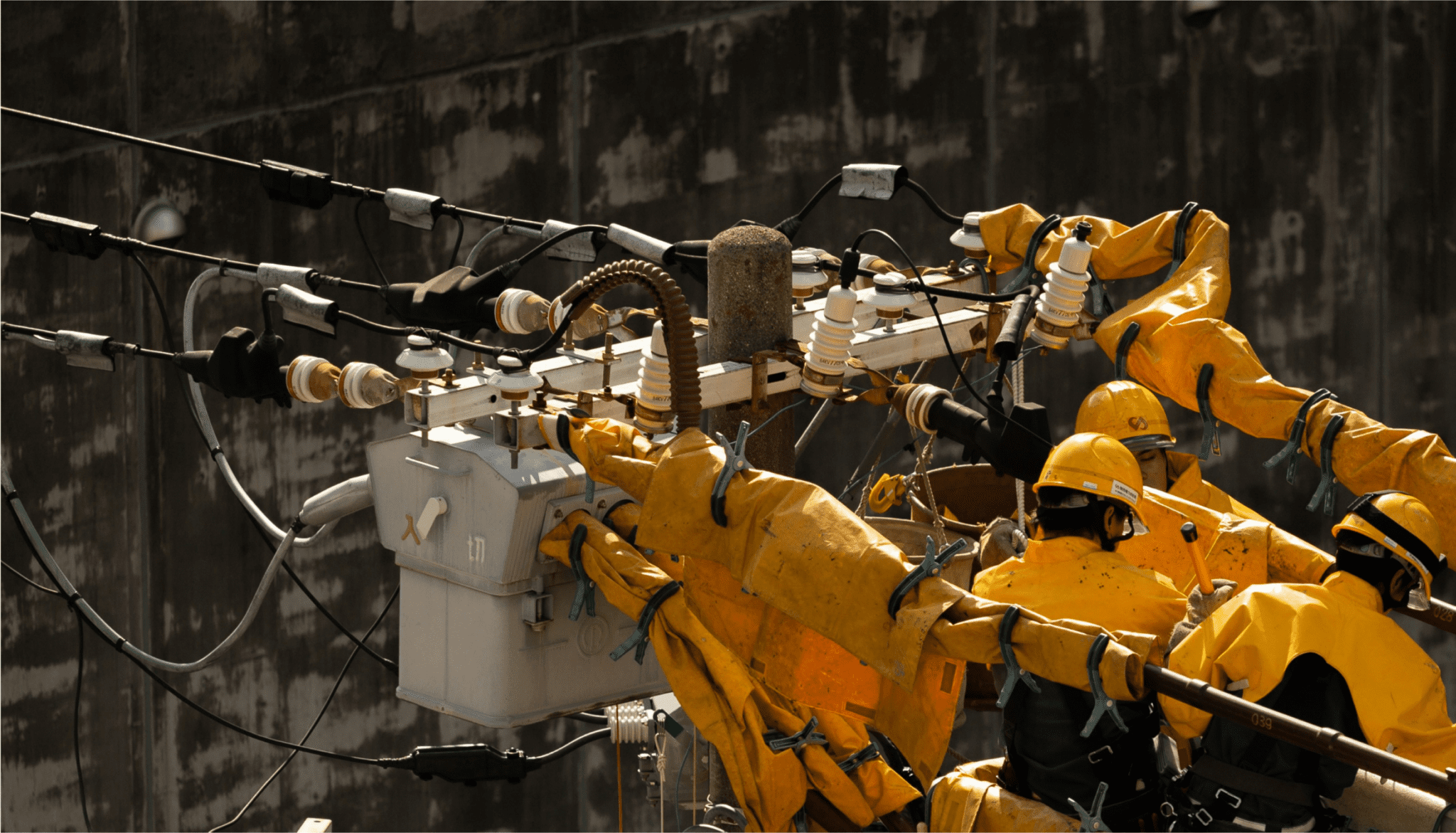

As the International Energy Agency (IEA) recently reported, scientists and policymakers increasingly agree that we will need all decarbonization tools at our disposal to have any hope of reaching net zero by 2050. We need widespread deployment of renewable resources for power generation. We need increased electrification and zero-carbon fuels for transportation. We need innovative technologies to take on carbon-intensive industries like chemicals, cement, and steel. We need to stop deforestation and reduce methane and nitrous oxide in agriculture.

But even all of that still won’t be enough to keep the tub from overflowing. We also need to capture and remove carbon. The IEA’s report shows that even if all countries meet their net-zero pledges on time and in full, we will exceed 1.5°C. The only way to keep 1.5°C within reach is to minimize how far we overshoot, and then bring temperatures back down through carbon removal. Otherwise, the math just doesn’t work. We’re going to need a mop.

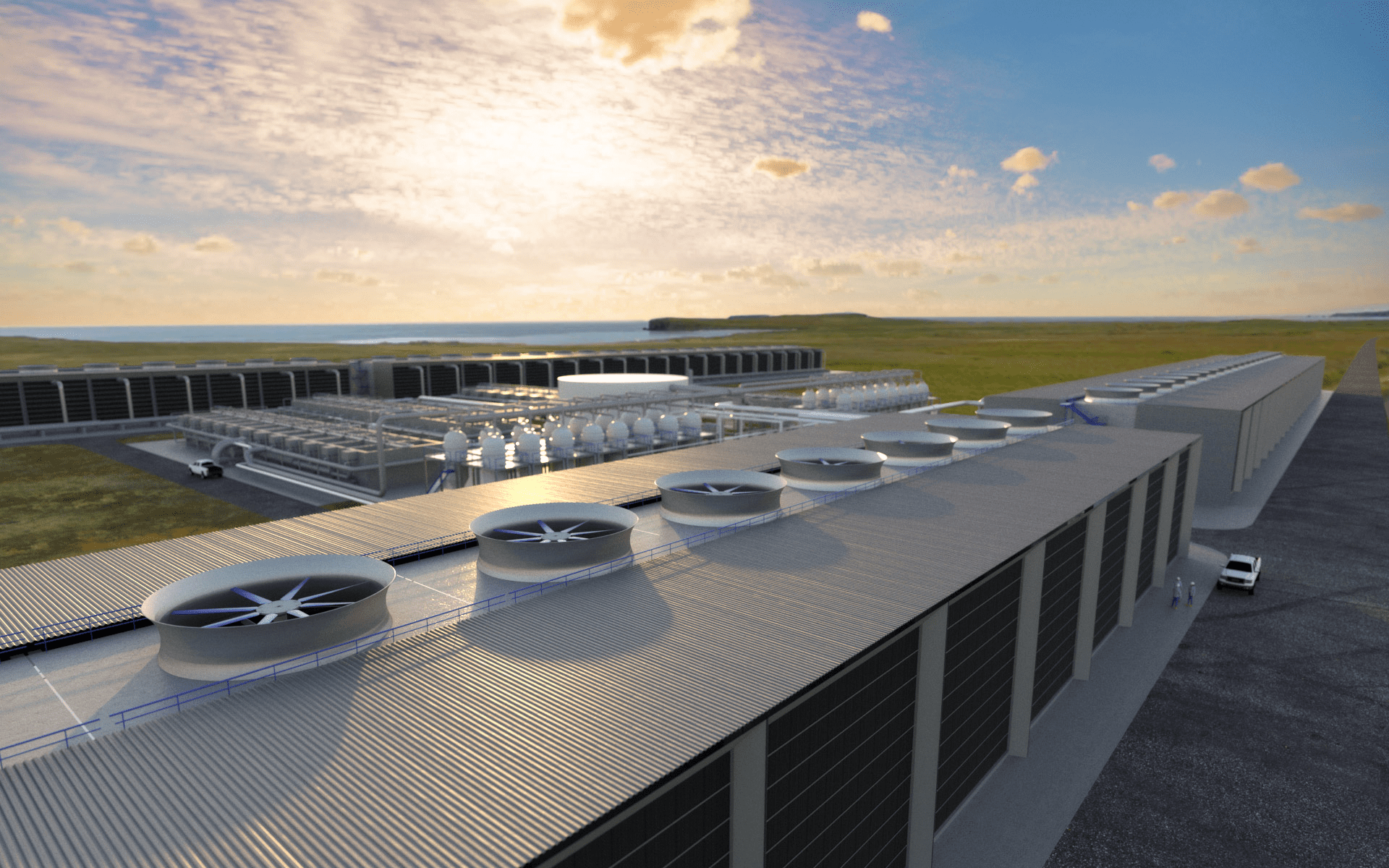

There are different ways to remove carbon from the atmosphere, but a technology called direct air capture (DAC) is among the most permanent and verifiable. DAC uses mechanical processes and chemical reactions to pull carbon dioxide from the air. What’s more, DAC facilities can take up relatively little space, remove millions of tons of carbon dioxide safely, and store it underground permanently.

So what’s the catch? DAC isn’t cheap. That’s part of the reason there are only two commercial-scale DAC facilities in the world right now. But those costs are expected to drop as deployment scales, and we’re already seeing massive investments in this emerging field.

Other methods of removing CO2 include planting trees, ocean alkalinity enhancement, and managing our soil and croplands more efficiently. However, the impact of these methods is much harder to measure and verify.

We also see promise in hybrid options that try to combine the low-costs of nature-based solutions with the verifiability and permanence of direct air capture, such as carbon casting and storing waste biomass.

Here's the bottom line: Carbon removal is critical to reducing and maintaining safe global temperatures. And yet, most experts expect the “global stocktake” report, one of the major required outcomes of COP28, will omit or greatly downplay the role of carbon removal given the political process that leads to the recommendations.

This would be a major missed opportunity to educate the world on the science and reality of the climate crisis we face. Despite its drawbacks, carbon removal is an essential tool to meet our climate goals. And when you need to solve a problem as quickly as possible, you want to have more, not fewer, tools available at your disposal. This is a both/and situation, not an either/or.

In December, world leaders can advance progress on carbon removal. This won’t be an easy task. But there’s no escaping the fact that if we aim to keep our planet to safe global temperatures, we must both turn off the faucet and mop up the floor.