One of the biggest obstacles to expanding clean energy in the United States is a lack of power lines. Building new transmission lines can take a decade or more because of permitting delays and local opposition. But there may be a faster, cheaper solution, according to two reports released Tuesday.

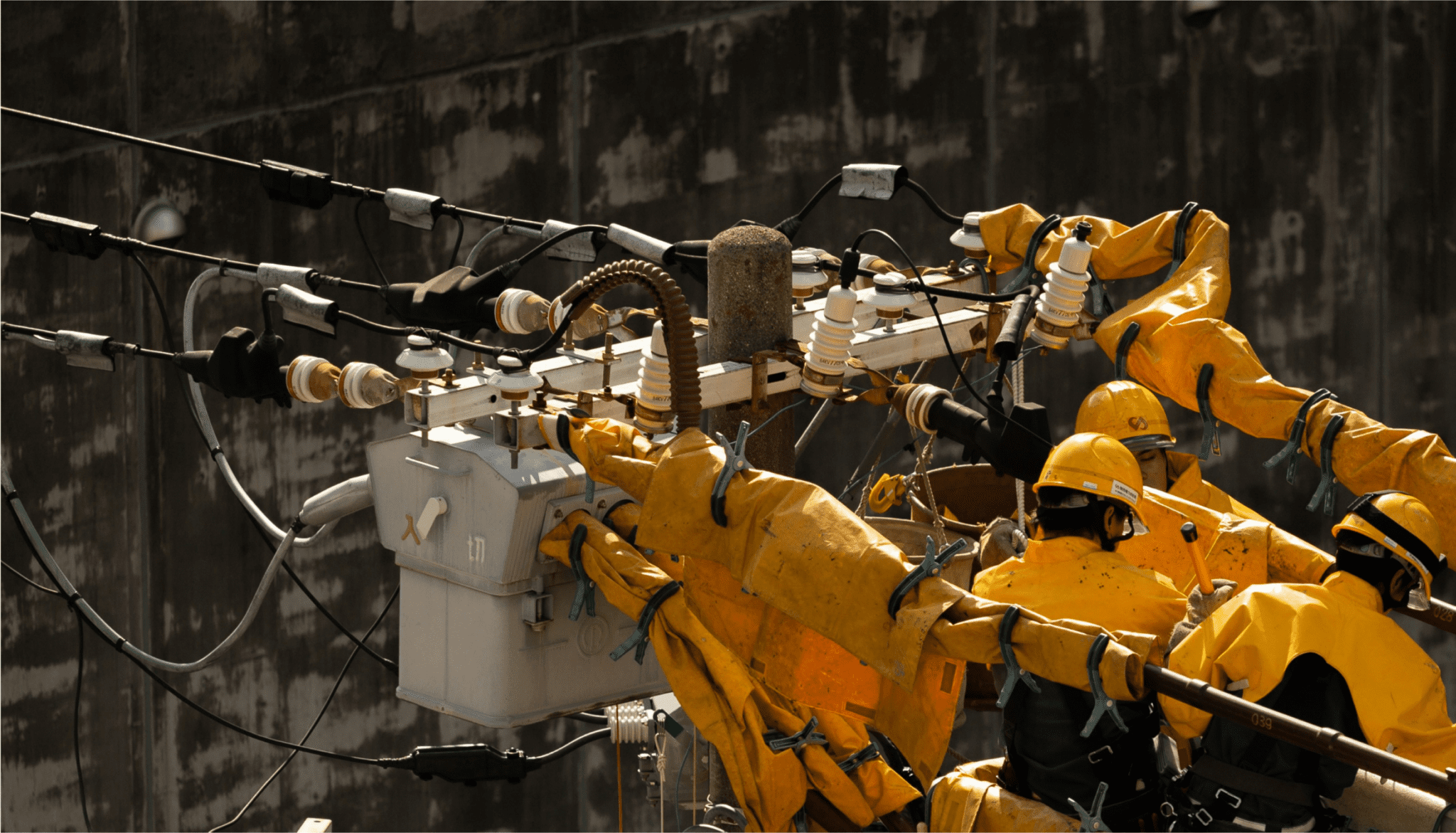

Replacing existing power lines with cables made from state-of-the-art materials could roughly double the capacity of the electric grid in many parts of the country, making room for much more wind and solar power.

This technique, known as “advanced reconductoring,” is widely used in other countries. But many U.S. utilities have been slow to embrace it because of their unfamiliarity with the technology as well as regulatory and bureaucratic hurdles, researchers found.

“We were pretty astonished by how big of an increase in capacity you can get by reconductoring,” said Amol Phadke, a senior scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, who contributed to one of the reports released Tuesday. Working with GridLab, a consulting firm, researchers from Berkeley looked at what would happen if advanced reconductoring were broadly adopted.

“It’s not the only thing we need to do to upgrade the grid, but it can be a major part of the solution,” Phadke said.

Today, most power lines consist of steel cores surrounded by strands of aluminum, a design that’s been around for a century. In the 2000s, several companies developed cables that used smaller, lighter cores such as carbon fiber and that could hold more aluminum. These advanced cables can carry up to twice as much current as older models.

Replacing old lines can be done relatively quickly. In 2011, AEP, a utility in Texas, urgently needed to deliver more power to the Lower Rio Grande Valley to meet soaring population growth. It would have taken too long to acquire land and permits and to build towers for a new transmission line. Instead, AEP replaced 240 miles of wires on an existing line with advanced conductors, which took less than three years and increased the carrying capacity of the lines 40%.

In many places, upgrading power lines with advanced conductors could nearly double the capacity of existing transmission corridors at less than half the cost of building new lines, researchers found. If utilities began deploying advanced conductors on a nationwide scale — replacing thousands of miles of wires — they could add four times as much transmission capacity by 2035 as they are currently on pace to do.

That would allow the use of much more solar and wind power from thousands of projects that have been proposed but can’t move forward because local grids are too clogged to accommodate them.

Installing advanced conductors is a promising idea, but questions remain, including how much additional wind and solar power can be built near existing lines, said Shinjini Menon, the vice president of asset management and wildfire safety at Southern California Edison, one of the nation’s largest utilities. Power companies would probably still need to build lots of new lines to reach more remote windy and sunny areas, she said.

“We agree that advanced conductors are going to be very, very useful,” said Menon, whose company has already embarked on multiple reconductoring projects in California. “But how far can we take it? The jury’s still out.”

Experts broadly agree that the sluggish build-out of the electric grid is the Achilles’ heel of the transition to cleaner energy. The Energy Department estimates that the nation’s network of transmission lines may need to expand by two-thirds or more by 2035 to meet President Joe Biden’s goals to power the country with clean energy.

But building transmission lines has become a brutal slog, and it can take a decade or more for developers to site a new line through multiple counties, receive permission from a patchwork of different agencies and address lawsuits about spoiled views or damage to ecosystems. Last year, the United States added just 251 miles of high-voltage transmission lines, a number that has been declining for a decade.

The climate stakes are high. In 2022, Congress approved hundreds of billions of dollars for solar panels, wind turbines, electric vehicles and other nonpolluting technologies to tackle global warming as part of the Inflation Reduction Act. But if the United States can’t add new transmission capacity more quickly, roughly half the emission reductions expected from that law may not materialize, researchers at the Princeton-led REPEAT Project found.

The difficulty of building new lines has led many energy experts and industry officials to explore ways to squeeze more out of the existing grid. That includes “grid-enhancing technologies” such as sensors that allow utilities to send more power through existing lines without overloading them and advanced controls that allow operators to ease congestion on the grid. Studies have found these techniques can increase grid capacity 10% to 30% at a low cost.

Countries such as Belgium and the Netherlands have been widely deploying advanced conductors to integrate more wind and solar power, said Emilia Chojkiewicz, one of the authors of the Berkeley report.

“We talked with the transmission system planners over there and they all said this is a no-brainer,” Chojkiewicz said. “It’s often difficult to get new rights of way for lines, and reconductoring is much faster.”

If reconductoring is so effective, why don’t more utilities in the United States do it? That question was the focus of the second report released Tuesday, by GridLab and Energy Innovation, a nonprofit organization.

One problem is the fragmented nature of America’s electricity system, which is actually three grids run by 3,200 different utilities and a complex patchwork of regional planners and regulators. That means new technologies — which require careful study and worker retraining — sometimes spread more slowly than they do in countries with just a handful of grid operators.

“Many utilities are risk averse,” said Dave Bryant, the chief technology officer for CTC Global, a leading manufacturer of advanced conductors that has projects in more than 60 countries.

There are also mismatched incentives, the report found. Because of the way in which utilities are compensated, they often have more financial incentive to build new lines rather than to upgrade existing equipment. Conversely, some regulators are wary of the higher upfront cost of advanced conductors — even if they pay for themselves over the long run. Many utilities also have little motivation to cooperate with one other on long-term transmission planing.

“The biggest barrier is that the industry and regulators are still caught in a short-term, reactive mindset,” said Casey Baker, a senior program manager at GridLab. “But now we’re in an era where we need the grid to grow very quickly, and our existing processes haven’t caught up with that reality.”

© 2024 The New York Times Company